Energy Flow And Connectivity

In Egyptian Works

In the Litany of Re, the cosmic creative force—being Re—is described as:

“The One Joined Together—who comes out of his own members”.

This is the perfect definition of the unity of multiplicities as the archetype of the created universe.

In order to ensure the function of a temple, a statue, etc. as a living organism, its components must be connected so that the cosmic energy can flow through unimpeded.

It is incorrect to merely think that a connection between two components/parts is only to ensure the structural stability of the part(s) and the whole building.

We can take clues from the human body (the house of the soul) when reviewing the Egyptian temple (the house of cosmic soul/energy/neter).

The human body is connected with muscles, etc., but veins and nerves are not interrupted at the bone joints of the skeleton. The living Ancient Egyptian temple was designed likewise.

The unity of the components of the temple must be like the components of the human body. The walls of a temple consist of blocks and corners, and such components (blocks) must be connected together in a way that allows the flow of divine energy, just like the parts of a human being.

Bas-reliefs of all sizes, as well as the hieroglyphic symbols, span two adjoining blocks with total perfection. The intent is very clear—to bridge over the joint between adjacent blocks next to each other, or on top of each other.

The blocks themselves were joined together in some type of nerve/energy system. A continuation of energy flow required special interlocking patterns.

The practice of joining blocks together prevailed in every Egyptian temple throughout the known history of Ancient Egypt. Here are a few examples of joining applications:

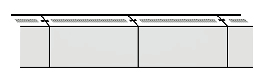

1. Cutting into each block of stone, a superficial, 1 inch (2cm) deep, dovetail-type notch that linked the stone to

the adjacent stone. These mortices link one block to another—a kind of nervous or arterial system running throughout the whole of the temple.

No binding material has ever been found in these shallow dovetail notches. There is no architectural or structural

importance, whatsoever, for such notches, with or without wooden tenons.

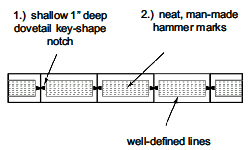

2. There are frequent, intentional, well-defined, rectangular, neat, man-made hammer marks on top of the blocks.

Again, these have no structural value whatsoever. [See illustration above]

3. Columns made of single, circular blocks have their sections connected with a well-defined circle of neat hammer

marks. Again, these have no structural value whatsoever. [See illustration below]

4. Columns built of semi-circular blocks (expressing duality) are found to have a superficial, 1″ (2cm) deep, dovetail-type notch between the two semi-circular blocks. Again, these notches are architecturally and structurally

meaningless.[See illustration above]

5. Paving blocks in and around Ancient Egyptian buildings are set in mosaic style, in order to avoid pointed

corners and continuous crack lines, such as the huge paving blocks around the pyramids of Giza. One can clearly see these very durable, perfectly fitted, square-angled blocks, which are several yards (meters) in length.

Ancient Egyptians, throughout history, avoided the simple abrupt interlocking joints. Creating uninterrupted continuous corners allowed the energies to flow unimpeded. Here are a few examples of joining applications, as found in various locations in Egypt:

1. In the Khafra Pyramid Valley Temple in Giza, near the Sphinx.

Many of the stones are set at different angles. This practice, which was common in Egyptian buildings, has no structural advantage over regular coursing. The additional calculations and labor involved in this type of jointing is considerable, and this Western notion of “design practicalities” or “economic consideration” should never be considered in Ancient Egypt.

The stone corners are not regular, interlocking dovetails, but rather, alternate inverse quoins. The joints go around the corners. To form such corners, the entire face of the stone has been carved away, in some cases dramatically, for over a foot (30 cm) – in other cases, barely creating a return of only an inch (2 cm) or so.

This unique method of creating corners was commonly used throughout Egyptian history. The purpose of the above unique feature is to avoid continuous cracks, so as to maintain the unity of the temple. As a result, the temple’s components must be connected so that the cosmic energy can flow throughout, unimpeded.

2. Also found in Saqqara from the Old Kingdom era.

After going to the entrance through the enclosure wall, we find the same jointing pattern techniques:

3. Further south into Egypt, at the Karnak Temples Complex, we find the same technique in jointing the blocks and depictions upon them.

4. As we go further south along the River Nile, we come to the Temple at Kom Ombo. Here again, we find hieroglyphic symbols spanning two adjoining blocks with total perfection.

At the end of this particular wall, we encounter the internal organic connections between the blocks of the temple walls. Here we find intentional, well-defined, neat, man-made hammer marks on the side of the blocks. Such work has absolutely no structural value whatsoever (and I say that with full authority, since I am a civil engineer with over 40 years of experience).

There are frequent, intentional, well-defined, rectangular, neat, man-made hammer marks on top of the blocks. Again, these have no structural value whatsoever. This intentional neat hammering is consistent with an organic, not a structural, purpose.

At the bottom of this particular temple wall, we encounter other organic design details. Cutting into each block of stone is a superficial 1-inch (2 cm) deep, dovetail-type notch that linked the stone to the adjacent stone. These mortises link one block to another—a kind of nervous or arterial system running throughout the whole of the temple.

More organic dovetail-type notches are found throughout. No binding material has ever been found in these shallow dovetail notches. There is no architectural or structural importance whatsoever for such notches, with or without wooden tenons. We also find frequent, intentional, well-defined, rectangular, neat, man-made hammer marks on top of the blocks. Again, these have no structural value whatsoever.

5. At the Luxor Temple, we find this organic jointing technique at the large seated granite statues. An inclined crack in the granite was “repaired” by providing two dovetail-type notches. The symbolic (or better yet, the organic) procedure is inescapable.

6. We find similar types statue jointing in the man-headed sphinxes that extend for 2 miles (3 km) between the Luxor and Karnak Temples.

7. On this impressive paved roadway between the two temples of Luxor and Karnak, we encounter another application of the organic jointing patterns in the paving blocks which are set in mosaic style in order to avoid pointed corners and continuous crack lines, such as the huge paving blocks around the pyramids of Giza. One can clearly see these very durable, perfectly fitted, square-angled blocks which are several yards (meters) in length.

8. Further north in the Giza Plateau, we find the same organic pattern on the causeway from the Khafra Pyramid to its Valley Temple next to the Sphinx.

9. The same patterns in perfectly-fitted huge paving blocks are found around the base of the Khafra Pyramid.

10. The same patterns are all over the Giza Plateau.

Ancient Egyptians, throughout history, avoided simple, abrupt, interlocking joints. Creating uninterrupted continuous corners allowed the energies to flow unimpeded.

[An excerpt from The Ancient Egyptian Metaphysical Architecture by Moustafa Gadalla]

https://egyptianwisdomcenter.org/product/the-ancient-egyptian-metaphysical-architecture/