“False Doors”—The Physical Metaphysical Threshold

On the western side of ALL Egyptian temples, shrines, and private tombs of all eras of the Ancient Egyptian history, there is always a crack in the wall—or what is commonly described as a false door.

The west is the point of entry of the departed spirit. It is the threshold between the physical earthly realm and the meta-physical realm.

The “false door” is basically a form of recessed wall with stone sockets similar in details to a regular door/window that is able to open and shut. The “false door” can take the form of ‘mehrab‘, a niche in the wall that may contain an effigy or a relic.

In divine temples, the false door is found at the very back of the sanctuary and acts as the interface between the divine and human spheres.

Incoming human action forms and directional flow ends at the false door, and the outflow of divine blessings begins and flows outwardly towards the temple’s entry.

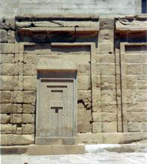

Looking, for example, at the massive temple at Medinet Habu on Luxor West bank—and looking at its Western Wall—

we find—the false door:

Further north at Abydos, we find a similar false door on its Western wall.

Likewise, at hundreds of tombs/ mastabas in the Giza plateau:

False doors are also found along the western walls of tombs in Saqqara:

The term ‘false door’ is itself something of a misnomer, as, from the Egyptian’s perspective, these features were fully functional portals by which the spirit of the deceased might leave or enter the inner tomb to receive the offerings presented to them.

Complementary features at false doors in tombs:

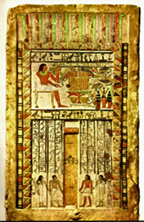

1. Most of these panels show the owner in standing or seated poses before a table of offerings. The figure of the owner is carved in a frontal aspect, stepping out over the threshold of the door. The reliefs of the deceased in a standing pose also appear on the jambs of the false door, thus representing the owner coming forth to receive the funerary offerings.

2. A table of offerings in front of the deceased figure is piled with sliced loaves of bread and simple texts enumerating various food and drink offerings which extend in range from the staple bread and beer to beef and fowl, vegetables, clothing, and sacramental oils. The altar, with its slices of bread, may be supplemented by other tables containing offerings or libation vessels.

3. Visitors are bringing the sacrificial animals and birds and cutting up the sacrificial bull at the door of the tomb. In the middle is the deceased man, seated under his pavilion (signifying a different realm) and receiving the sacrifice.

4. Behind the door is the main burial shaft. The main shaft led from the middle of the roof of the mastaba to the burial chamber.

The Festival Meetings At The “False” Doors

On festivals and days of offering, when the visitors presented the banquet with the customary rites, this great painted figure, in the act of advancing, and seen by the light of flickering torches or smoking lamps, might well appear endowed with life. It was as if the deceased ancestor himself stepped out of the wall and mysteriously stood before his descendants to claim their homage. The inscription on the lintel repeats, once more, the name and rank of the deceased. Faithful portraits of him and of other members of his family figure in the bas-reliefs on the door posts. Scenes depict him seated tranquilly at a table with the details of the feast carefully recorded at his side, from the first moment when water is brought to him for ablution to that when, all culinary skill being exhausted, he has but to return to his dwelling in a state of beatified satisfaction.

By the divine favor, the soul (or rather the doubles [Ka-s] of the bread, meat, and beverages) passed into the other world and there refreshed the human double [Ka]. It was not, however, necessary that the offering should have a material existence in order to be effective. The first comer who should repeat aloud the name and the formulas inscribed upon the stone secured for the unknown occupant, by this means alone, the immediate possession of all the things which he enumerated.

[An excerpt from The Ancient Egyptian Metaphysical Architecture by Moustafa Gadalla]