The Egyptian Knowledge Of Metallurgy And Metalworking

1. The Egyptian Knowledge Of Metallurgy And Metalworking

The Egyptians learned how to work metals from an early period, and all agree that 5,000 years ago, the Ancient Egyptians had already developed the techniques of mining, refining, and metalworking.

Ancient Egypt did not have several kinds of mineral ores, such as silver, copper, tin, lead, etc., even though they produced large quantities of electrum (an alloy of gold and silver), copper, and bronze alloys. The Ancient Egyptians used their expertise to explore for mineral ores in Egypt and in other countries. Ancient Egypt had the means and knowledge to explore for needed mineral ores, establish mining processes, and transport heavy loads for long distances by land and sea.

Because it being was largest and richest population in the ancient world, Egypt imported huge quantities of raw materials; and in return exported large quantities of finished goods. The Ancient Egyptians’ finished metallic and non-metallic products are found in tombs throughout the Mediterranean Basin, European, Asiatic and African countries.

The Egyptians possessed considerable knowledge of chemistry and the use of metallic oxides, as manifested in their ability to produce glass and porcelain in a variety of natural colors. The Ancient Egyptians also produced beautiful colors from copper, which reflects their knowledge of the composition of various metals, and the knowledge of the effects produced on different substances by the Earth’s salts. This concurs with our “modern” definition of the subjects of chemistry and metallurgy.

- Chemistry is the science dealing with the composition and properties of substances, and with the reactions by which substances are produced from or converted into other substances; the application of this to a specified subject or field of activity; and the chemical properties, composition, reactions, and uses of a substance.

- Metallurgy is the science of metal; especially the science of separating metals from their ores and preparing them for use by smelting, refining, etc.

The methods of metalworking – melting, forging, soldering, and the chasing of metal – were not only much practiced, but also most highly developed. The frequent references of metalworking in Ancient Egyptian gives us a truer conception of the importance of this industry in Ancient Egypt.

The skill of the Egyptians in compounding metals is abundantly proven by the vases, mirrors, and implements of bronze, discovered at Luxor (Thebes) and other parts of Egypt. They adopted numerous methods for varying the composition of bronze through a judicious mixture of alloys. They also had the secret of giving a certain degree of elasticity to bronze or brass blades, as evident in the dagger now housed in the Berlin Museum. This dagger is remarkable for the elasticity of its blade and its neatness and perfection of its finish. Many Ancient Egyptian products, now scattered in European museums, contain 10 to 20 parts tin to 80 and 90 parts copper.

Their knowledge of metal ductility is evident in their ability to manufacture metallic wires and threads. Wiredrawing was achieved with the most ductile metals such as gold and silver, as well as brass and iron. Gold thread and wire were the result of wire-drawing, and there is no instance of them being flattened. Silver wires were found in the tomb of Twt Homosis (Tuthomosis) III and gold wires were found attached to rings bearing the name of Osirtasen I, who lived 600 years before Twt Homosis III [1490–1436 BCE].

The Egyptians perfected the art of making thread from metals. It was fine enough for weaving into cloth, and for ornamentation. There exists some Amasis delicate linen with numerous figures of animals worked in with gold threads, which required a great degree of detail and finesse.

The science and technology to manufacture metallic products and goods were known and perfected in Ancient Egypt, which was able to produce numerous metallic alloys in large quantities. Examples of the manifestation of their knowledge are shown next.

2. The Golden Silver (Electrum) Products

The Ancient Egyptians utilized gold, which was mined in Egypt. They also used silver, which was/is not found in Egypt, but was imported from the Iberian Peninsula. They used silver individually or combined into the golden-silver alloy known as electrum. Ancient Egyptian records indicate that the neteru (gods/goddesses) are made from electrum, the source of energy in the universe. In addition to making religious objects such as statues, amulets, etc., this amalgam was often used for personal adornment and for ornamental vases. The proportion of gold to silver was generally two to three. An Ancient Egyptian papyrus from the time of Twt Homosis III (1490-1436 BCE) indicates that an official received a “great heap” of electrum, which weighed 36,392 uten, i.e. 7,286 lbs. [3,311 kg. 672 g.].

Gold and silver were also cast to make small statues, in the same manner as copper and bronze. The two metals are often found in the form of solid beads, which are at least 6,000 years old.

At the Middle Kingdom tombs of Beni Hassan, the scenes give a general indication of the goldsmith’s trade. The process of washing the ore, smelting or fusing the metal with the help of the blow-pipe, fashioning it for ornamental purposes, weighing it, recording materials inventories, and other vocations of the goldsmith are all represented in these tombs.

When the gold was not cast solid, it was flattened into a sheet of even thickness. Gold in sheet form was used to decorate wooden furniture. Thicker gold sheets were hammered directly onto the wood and fixed by small gold rivets. Thinner sheets were attached by an adhesive, probably glue, on a prepared base of plaster. Very fine sheets were used as a coating for statues, mummy masks, coffins, and other items. It was applied over a layer of plaster, but the nature of the adhesive used by the Egyptian craftsman has not been identified.

The ability to work large masses of the material is shown in the 300-lb. [136 kg.] gold coffin of Twtankhamen, now displayed at the Cairo Museum.

3. The Copper And Bronze Products

Ancient Egypt lacked mineral ores to produce copper and bronze alloys—copper, arsenic, and tin—which were obtained abroad. The Ancient Egyptians manufactured large quantities of these alloys more than 5,000 years ago.

Egyptian copper was hardened by the addition of arsenic. The content of arsenic in the copper alloy varied, depending on the intended use. Variations in composition have been observed: for example, daggers and halberds had stronger cutting edges and contained 4% arsenical copper, while axes and points contained 2% arsenical copper. Arsenical copper was used from the pre-dynastic times [c. 5000 BCE] right up to and including the Middle Kingdom [2040–1783 BCE].

The Ancient Egyptian stone (known as the “Palermo Stone” and now housed in the Palermo Museum) records the making of a copper statue of Khasekhemwy of the 2nd Dynasty [c.2890–2649 BCE]. A copper statue of Pepi I [2289-2255 BCE], the earliest surviving example of metal sculpture, is presently housed in the Cairo Museum. It is undoubtedly the precious nature of all metals in Egypt that explains the rarity of early pieces, since much of the metal would eventually have been melted down and reused several times.

In addition to manufacturing arsenic copper, the Ancient Egyptians also manufactured bronze products. The addition of a small proportion of tin to copper produces bronze and results in a lower melting point, an increased hardness, and a greater ease in casting. The content of tin varies widely between 0.1% and 10% or more. Many bronze items of a very early period have been found. A cylinder bearing the name of Pepi I [2289–2255 BCE], showing clean-cut lines as well as other bronze articles of the same period, indicates that the molding of bronze items dates to earlier than 2200 BCE.

The bronze industry was very important for the country. Bronze was perfected and employed in Egypt for large vessels as well as for tools and weapons. There are numerous examples of perfected bronzes that come from all periods since the Old Kingdom [2575–2150 BCE], such as the Posno Collection, which is now housed at the Louvre in Paris.

Ancient Egyptian bells of various kinds were found, carefully wrapped in cloth before they were placed in tombs. A large number of these bells are now housed in the Cairo Museum.

Bells were made mainly of bronze, but were also occasionally made of gold or silver. They came in different forms. Some have the form of bells with a jagged mouth, which represents a flower calyx, among a whole line of other types. The large number of Ancient Egyptian bell molds [now in the Cairo Museum, cat. #32315 a, b] provides good evidence of metal founding in Ancient Egypt. The influx hole for the liquid metal can be clearly seen in these molds. The chemical analysis of the typical Ancient Egyptian bell was found to be 82.4% copper, 16.4% tin, and 1.2% lead.

The Egyptians employed various kinds of bronze alloys, as we learn from the texts of the New Kingdom, where there is frequent mention of “black bronze” and the “bronze in the combination of six” – i.e., a six-fold alloy. Such variations produced different colors. Yellow brass was a compound of zinc and copper. A white (and finer) kind of brass had a mixture of silver, which was used for mirrors and is also known as “Corinthian brass”. Adding copper to the compound produced a yellow, almost golden appearance.

Copper and bronze provided material for a wide range of domestic utensils such as cauldrons, pitchers, basins, and ladles, in addition to a wide range of tools and weapons: daggers, swords, spears, and axes, as well as battleaxes. In the Old and Middle Kingdoms, rounded and semicircular forms of battle-axes predominated.

Records from the Middle Kingdom Period [2040–1783 BCE]—such as those depicted in Beni Hassan tombs – show the variety of Ancient Egyptian weapons, such as the various shields depicted herein, with several variations of riveting.

During the New Kingdom [1550–1070 BCE], the Ancient Egyptians raised a large military in order to protect their borders. The Egyptians hired mercenaries for their military forces and the Egyptians manufactured their necessary fighting equipment.

A secure and prosperous Egypt was able to produce large quantities of metal goods in the 18th Dynasty [1575–1335 BCE]. This increase in the number of goods corresponded to the increase in mining activities and an increase in number of Egyptian copper and bronze items in Iberian tombs of the same period, as is referenced at the end of the next chapter.

The Ancient Egyptian demand for large quantities of copper, arsenic, and tin developed more than 5,000 years ago. The three mineral ores were imported from the only source known in the ancient world—Iberia.

Archaeological records show the early utilization of mineral wealth, in southern Iberia, of copper and arsenic. As for the tin, we are aware of the “Tin Route” which ran along the western coast of the Iberian Peninsula, where the tin came from Galicia and possibly Cornwall. Strabo, in Vol. 3 of his Geography, tells us that:

Tin . . . is dug up; and it is produced both in the country of the barbarians who live beyond Lusitania, and in the Cassiterides Islands; and tin is brought to Massilia from the British Islands.

Evidence of early contacts along the “Tin Route” that came from the eastern Mediterranean region—namely Ancient Egypt—is shown in our book Egyptian Romany: The Essence of Hispania, by Moustafa Gadalla.

4. The Glazing (Glass and Glazing) Products

The Ancient Egyptians produced numerous types of glazed articles as early as the Pre-Dynastic Period [c. 5000 BCE]. Glazed objects from this early time were mostly beads, with solid quartz or steatite being used as a core. Steatite was used for carving small objects like amulets, pendants, and small figures of neteru (gods/goddesses), as well as for a few larger articles, and it proved an ideal base for glazing. Glazed steatite objects are found throughout the Dynastic Period [3050–343 BCE], and it is by far the most common material for scarabs. The same glazing techniques were used to mass produce funerary equipment (amulets, shabti-figures) and house decoration (tiles and inlays of floral patterns).

The variety and high quality of Ancient Egyptian glazing articles are indicative of the Ancient Egyptian knowledge of metallurgy. The most common colors of the Egyptian glaze were blue, green, or bluish-green. The color is the result of adding a copper compound. More brilliant results were achieved by using a mixture of copper and silver.

Ancient Egyptian glass was formed by strongly heating quartz sand and natron with a small mixture of coloring agents such as a copper compound or malachite, to produce both green and blue glass. Cobalt, which would have been imported, was also used. After the ingredients were fused into a molten mass, the heating ceased when the mass reached the desired properties. As the mass cooled, it was poured into molds and rolled out into thin rods or canes, or other desired forms.

Glass blowing is shown at the tombs of Ti [2465–2323 BCE], at Saqqara, Beni Hassan (more than 4000 years ago) and other later tombs.

Since glaze contains the same ingredients fused in the same manner as glass; glassmaking may therefore be attributed to the Egyptians even at a much earlier date. The hard, glossy glaze is of the same quality as glass. The technique that was applied to the making of glass vessels was a natural development in the technique of glazing.

Egyptian glass bottles are shown on monuments of the 4th Dynasty [2575–2465 BCE]. Egyptian glass bottles of various colors were exported into other countries such as Greece, Etruria, Italy, and beyond.

The Ancient Egyptians displayed their excellent knowledge of the various properties of materials in the art of staining glass with diverse colors, as evident from the numerous fragments

found in the tombs at Luxor (Thebes). Their skill in this complicated process enabled them to imitate the rich brilliance of precious stones. Some mock pearls have been so well counterfeited that even now it is difficult. with a strong lens. to differentiate them from real pearls. Pliny confirmed that they succeeded so completely in the imitation as to render it difficult to distinguish false from real stones.

The spectrum of colors in these semi-precious stones is fascinating. It ranges from the limpid blue of lapislazuli to the turbulent blue of turquoise and the speckled gold of cornaline; these being the three stones that are most representative of the Egyptian jeweler’s art. But there was also agate, amethyst, and haematite. In addition, we should note that Egyptian craftsmen worked wonders with enamel; large plaques of which were decorated with hieroglyphs or cartouches.

Glass mosaics were made of various parts which were made separately and then united with heat by applying a flux. The Ancient Egyptian glass mosaics have wonderful, brilliant colors.

Glass is frequently found in what is commonly called Egyptian cloisonné work; a term used to describe an inlay consisting of pieces of glass, faience, or stone set in metal cells and fixed with cement. The process consisted of putting powdered glass in the cloison and applying enough heat to melt the powder until it became a compact mass.

Glazed pottery, tiles, and other ceramics were major industries in Ancient Egypt. Some tiles had high glazes and designs in an intense blue. They also produced ceramics with an iridescent metallic sheen.

An elegant Egyptian faience

bowl, now in the Berlin

Museum, decorated with a

painting of three fish with one

head,and three lotus flowers.

Some tiles were painted in pigments made by mixing metallic oxides (of copper, manganese, cobalt, etc.) and alkaline silicates with water. Glazed tiles of the highest quality are to be found in Saqqara from about 4,500 years ago. The “Southern Tomb”, only 700 ft. [300 m] from the Step Pyramid, was discovered unmolested at Saqqara by Lauer and Firth in 1924-26. It consists of several chambers lined with blue tiles exactly like the burial chambers of the Step Pyramid.

5. The Iron Products

Although the pyramids were built before the “bronze and iron ages”, meteoric iron was known to the Egyptians of the Pyramid Age. The Ancient Egyptian name for iron was bja. The word bja is mentioned repeatedly in the Unas Funerary (Pyramid) Texts (UFT)that are found in the Saqqara Complex (about 4,500 years ago) in

connection with the ‘bones’ of the star kings:

I am pure, I take to myself my iron (bja) bones, I stretch out my imperishable limbs which are in the womb of Nut. . . [UFT 530]

My bones are iron (bja) and my limbs are the imperishable stars. [UFT 1454]

The King’s bones are iron (bja) and his limbs are the imperishable stars. . . [UFT 2051]

Iron was utilized in Ancient Egypt, and iron mines can be found in the Egyptian desert. Herodotus mentions iron tools being used by the builders of the pyramids. Herodotus’ account is confirmed by pieces of iron tools embedded in old masonry which were discovered by 19th century Egyptologists in various places. Also, the monuments of Luxor (Thebes) and even the tombs around Memphis, dating more than 4,000 years ago, represent butchers sharpening their knives on a round bar of metal attached to their apron which, from its blue color, can only be steel. The distinction between the bronze and iron weapons in the tomb of Ramses III – one painted red, the other blue – leaves no doubt of both having been used at the same periods.

Homer distinctly mentioned the use of iron in Iliad [xxiii, 261], describing how the red hot metal hisses when it is submerged in water.

Academia’s arbitrary dating of “metal developments” (copper, bronze, iron, etc.) ages is absolutely baseless. Bronze articles of various kinds such as swords, daggers, other weapons, and defensive armor were in continuous use by all nations long after iron was known and used by them. Western academia cavalierly denies Egyptian knowledge and use of iron products because the Ancient Egyptians never abandoned the use of bronze items. Yet, the discovery of Greek and Roman arms and tools made of bronze was never used by Western academicians to claim the Greek and Roman ignorance of iron. It is therefore that the knowledge and production of Ancient Egyptian iron products can’t be arbitrarily ignored.

6. The Egyptian Mining Experience

In the orderly nature of the Ancient Egyptian civilization, they maintained written records showing the nature of their expeditions and the arrangements of their mining activities. The surviving Ancient Egyptian records show a tremendous organization of mining activities more than 5,000 years ago, in numerous sites throughout Egypt and beyond.

The turquoise mines at Serabit el Khadem in the Sinai Peninsula show a typical Ancient Egyptian mining quarry consisting of a network of caverns and horizontal and vertical passages carefully cut with proper corners—as were the quarries of the Ancient Egyptians in all periods. The Ancient Egyptians were able to cut deep and long into the mountains with proper shoring and support of excavated shafts and tunnels. Underground water seepage into tunnels and shafts was safely pumped out to ground level. These Egyptian pumps were famed worldwide, and were used in the mining activities in Iberia as per the following testimony of Strabo, in his Geography [3. 2. 9]:

So Poseidonius implies that the energy and industry of the Turdetanian miners is similar, since they cut their shafts aslant and deep, and, as regards the streams that meet them in the shafts, oftentimes draw them off with the Egyptian screw.

The very religious Egyptians have always built temples/shrines, along with commemorative stelae, near/at each mining site. The same exact practice was found in mining sites outside of Egypt, such as in the Iberian Peninsula, where mines of silver, copper, etc. were extracted since time immemorial.

The Ancient Egyptian mining site at Serabit el Khadem in Sinai provides a typical mining site with its small temple of Hathor, called “the Lady of the Turquoise”, which stood on a high rocky terrace that dominates the valley since the 4th Dynasty [2575–2465 BCE], or possibly much earlier. This temple was enlarged afterwards by the kings of the New Kingdom; especially by Twt Homosis III. In front of the temple, for at least a half mile, is a kind of avenue that was arranged through numerous massive stelae covered on four sides with inscriptions commemorating mining expeditions. Inscribed stelae are also found at other mines throughout Egypt, describing the work at each mining site.

At the mines of Wadi Maghara, in Sinai, the stone huts of the workmen as well as a small fort, built to protect the Egyptians stationed there from the attacks of the Sinai Bedouins, still stand. There was a water well not far from these mines, and sizeable cisterns in the fortress to hold water. The mines of Wadi Maghara were actively worked all throughout the dynastic era [3050–343 BCE].

Inscriptions of the 19th Dynasty in the desert temple of Redesieh relate that King Seti I [1333–1304 BCE] commissioned stonemasons to dig a water well to provide water for both the mining operations as well as the mining workers. When the well was finished, a station and “a town with a temple” were built. Ramses II [1304–1237 BCE], his successor, mediated plans to provide for boring additional water along the roads to mining sites, where it was also needed.

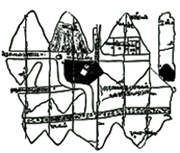

Each mining site was conceived and planned for, with actual plans drawn up. Two Ancient Egyptian papyri were found which include site maps related to mining for gold during the reigns of the Pharaohs Seti I and Ramses II. One papyrus, which is only partially preserved, represents the gold district of the mountain Bechen in the Eastern Desert, and belongs to the time of Ramses II. The site plan on the found papyrus depicts two valleys running parallel to each other between the mountains. One of these valleys, like many of the larger valleys of the desert, is covered with underwood and blocks of stone to control soil erosion as a result of surface water runoff.

The prepared site plan shows the major details of the site, such as the road network within the mining site and its connection to the outer roadway system and “routes leading to the sea”. The site plan also shows treatment areas of ore metals (such as washing, etc.), small houses, storage areas, various buildings, a small temple, a water tank, etc. The area surrounding the mining site shows cultivated ground that provides the food needed for the mining site colony.

The Ancient Egyptian records also show the various divisions and specialties of the manpower at mining sites.

The Ancient Egyptian records show the organizational structure of the mining operations. Ancient Egyptian surviving records show the names and titles of various officials who, during the Old and the Middle Kingdoms, directed the works at Hammamat, at the Bechen mines in the Eastern Desert. They included engineers, miners, smiths, masons, architects, artists, security details, and ship captains who maintain the integrity of the parts of the ships that will be put back together when the expedition reaches navigable waters.

The ore metals were treated on site before being transported by land and water, under heavy security, to the populated areas of Egypt by the Nile Valley.

Egyptian mining activities were very organized, with people traveling back and forth to check the site work, ensuring the proper efficiency of operation and providing frequent rotation of the workforce at the mining sites, as well as providing amenities to these fortified sites. Under the Ancient Egyptian King Pepi I [2289–2255 BCE], the records show the name of the director of the quarries and the names and titles of the higher officials who conducted inspection visits to the site. Inscriptions mention many titles, such as “the chief superintendent of all the works” and “the chief architect”. This great man paid two inspection visits to Hammamat—once accompanied by his deputy; and once, when it was a question of the religious texts on the walls of a temple, with a superintendent of the commissions of the sacrificial estates.

A document that dates to the reign of Ramses IV [1163–1156 BCE] provides a report of an expedition to the mountain of Bechen in the Eastern Desert under the direction of the “superintendent of the works”. Altogether, the expedition consisted of 8,368 people. These men included more than 50 civil officials and ecclesiastics as well as 200 officials from various departments. The fieldwork was carried out by miners, stonemasons, and other related work forces who worked under three superintendents and the “chief superintendent”. The labor work was carried out by 5000 miners, smiths, masons, etc., and 2,000 various types of labor. There were at least 110 officers supervising 800 of the barbarian mercenaries used for security details. The security forces were needed for the protection of the mining sites and the transportation of people and material. The management of this large number of people is extraordinary—8,368 people is the size of a large community, even nowadays.

The Ancient Egyptians sought raw materials from other countries and used their homegrown expertise to explore, mine, and transport raw materials from all over the inhabited world. Ancient Egyptian mining characteristics are found in many places—such as Iberia.

[से एक अंश प्राचीन मिस्र: संस्कृति का खुलासा, दूसरा संस्करण मुस्तफ़ा गदाल्ला द्वारा]

https://egyptianwisdomcenter.org/product/--/