[anuvaad lambit hai]

[Devanaagaree mein upalabdh hai: मिस्री-ज्ञान-केंद्र.भारत]

The Synthetic Concrete Blocks Of The Pyramids

1. Herodotus And Pyramid Construction

Herodotus neither mentioned the source of the core masonry as local limestone nor that the pyramid blocks were carved. He stated that stones (not necessarily quarried blocks, but possibly stone rubble) were brought to the site from the east side of the Nile.

Here is an excerpt from Herodotus’ account:

“This pyramid was built thus; in the form of steps, which some call crosae, and others call bomides. After preparing the foundation, they raised stones by using machines made of short planks of wood, which raised the stones from the ground to the first range of steps. On this range there was another machine which received the stone upon arrival. Another machine advanced the stone on the second step. Either there were as many machines as steps, or there was really only one, and portable, to reach each range in succession whenever they wished to raise the stone higher. I am telling both possibilities because both were mentioned.”

The term mechane, used by Herodotus, is a nonspecific, generic term indicating a type of device. When the word mechane is translated to mean a device such as a (short blank wooden) mold, the whole description makes sense.

Let us review it in such a form:

“… They raised stones by using molds made of short planks of wood, which raised the stones from the ground to the first range of steps. On this range there was another mold which received the stone [rubble] upon arrival. Another mold advanced the stone on the second step. Either there were as many molds as steps, or there was really only one, and portable, to reach each range in succession whenever they wished to raise the stone higher. I am telling both possibilities because both were mentioned.

A mold can be considered as an apparatus or device. If Herodotus was not familiar with the term ‘mold’, he therefore used the more general term, ‘mechane’.

These wooden plank molds have been used in Egypt in various degrees as a molding apparatus to hold the manmade concrete in block-shaped form until the concrete dried.

Δ Δ Δ

2. Synthetic And Natural Blocks

The facts show that these Egyptian pyramid blocks were high-quality, man-made limestone concrete, not quarried natural stone.

The characteristics of the pyramid blocks in Giza are consistent with man-made molded concrete blocks, and can never be of a natural quarry stone.

The case at the Khafra Pyramid gives us the visual evidence.

Since the original ground at the Khafra Pyramid was sloping, it was necessary to make it level for the base. As a result, the Egyptians cut the natural ground to provide a level base.

You can see the original natural rock of the Giza Plateau. The natural stone has the normal characteristics of formed strata. Strata and defects make it impossible to cut stone to perfectly uniform dimensions. Natural stone consists of fossil shells which lie horizontally or flat in the bedrock, as a result of forming sedimentary layers of bedrock over millions of years.

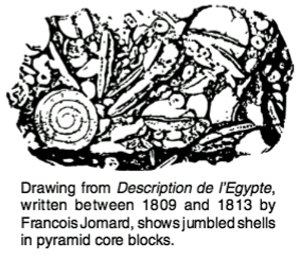

Next to this exposed bedrock of the Giza Plateau, we can see the formation of the pyramid block that contains no strata whatsoever. The blocks of the masonry pyramids of Egypt show jumbled shells, which are indicative of man-made cast stone. In any concrete, the aggregate are jumbled; and as a result, cast concrete is devoid of sedimentary layers.

These pyramids consisted essentially of fossil shell limestone, a heterogeneous material very difficult to cut precisely.

A closer look at the pyramid blocks—like this one—shows us that the top layers of several blocks are quite riddled with holes. The deteriorated layers look like sponges. The denser bottom layer didn’t deteriorate.

In a concrete mix, air bubbles and excess watery binder rise to the top, producing a lighter, weaker form. The rough top layer is always about the same size, regardless of the height of the block.

This phenomena is evident at all the pyramids and temples of Giza; i.e. light weight, weathered and weak top portions, which is indicative of cast concrete, and not natural stone.

Δ Δ Δ

The synthetic blocks consist basically of about 90-95% limestone rubble and 5-10% cement.

It is a known fact that the Ancient Egyptian silico-aluminate cement mortar is far superior to present day hydrated calcium sulfate mortar. By mixing the ancient high quality cement with fossil-shell limestone, the Egyptians were able to produce high quality limestone concrete.

All the required ingredients to make synthetic concrete stone, with no appreciable shrinkage, are plentiful in Egypt:

1. The alumina, used for low temperature mineral synthesis, is contained in the mud from the Nile River.

2. Natron salt (sodium carbonate) is very plentiful in the Egyptian deserts and salt lakes.

3. Lime, which is the most basic ingredient for cement production, was easily obtained by calcining limestone in simple hearths.

4. The Sinai mines contained arsenic minerals, needed to produce rapid hydraulic setting, for large concrete blocks. Natron (a type of flux) reacts with lime and water to produce caustic soda (sodium hydroxide), which is the main ingredient for alchemically making stone.

Records about the source of the arsenic minerals that were used to manufacture the stone are found in Sinai, such as at Wadi Maghara.

Records of mining activities during Zoser’s reign are indicated on a stele at the mines of Wadi Maghara in Sinai. Similar mining activities, during the subsequent Pharaohs’ reigns of the 3rd and 4th Dynasties, are also recorded at Sinai.

[For more information about the extensive mining activities in Ancient Egypt as well as advanced Ancient Egyptian knowledge of metallurgy and metal alloy fabrication of all types, read Ancient Egyptian Culture Revealed by Moustafa Gadalla.]

Δ Δ Δ

3. Synthetic Concrete Blocks Various Types

A man-made concrete is defined as building material made of sand and gravel, bonded together with cement into a hard, compact substance and used in making bridges, road surfaces, etc.

There are countless concrete mixes with varied ratios of the main ingredients: aggregate, cement, water and admixtures. Various applications require different concrete mixes. The Ancient Egyptians utilized a wide variety of concrete mix applications. Examples:

In the Giza Plateau, we can find three types of concrete.

At the Khufu Pyramid, for example, there are three types in the interior pyramid blocks and the exterior angled blocks, as well as the paving blocks around the pyramid site.

The interior pyramid blocks were not intended to be exposed to natural elements. Therefore, they were not finely graded. In other words, they were the bulk-type variety. When the exterior blocks were stripped away, these interior blocks were exposed to the natural elements. Over the years, they have deteriorated rapidly.

The exterior blocks were intended to withstand the natural elements and therefore were made of more finely graded stones, as we can see here from this photograph at the Khafra Pyramid in Giza.

Mastabas throughout the Giza Plateau utilized this strong exterior-type concrete mix in their walls, as shown here in this mastaba-type tomb next to the Great Pyramid.

The third type of concrete mix that we can find at the Giza site is in the paving blocks that surround the base of the pyramid.

The exposed paving blocks at the Great Pyramid site show us a finely graded concrete of a quality that can withstand abrasion forces caused by traffic.

At the Khafra Pyramid site, the paving blocks are in much better shape. They have maintained their superior qualities for thousands of years.

Another application of concrete mixes is the type used by the Egyptians to build their arches and vaulted ceilings. Vaulted ceilings are found, since the Old Kingdom, in Menkaura Pyramid (in Giza) and Mastabat Faroon (in Saqqara).

Construction details and quality are found in the Abydos Temple.

Egyptian roofing included various curvatures, just as one can find in the Hatshepsut Temple—Anubis Shrine.

A fourth type of concrete block was used as a harbor water break in Alexandria’s outer harbor wall. It predates Alexander, as stated in Greek and Roman classical writings. These were designed to withstand the continuous water pressure forces of waves as well as the effects of salt in the water.

One of the seven wonders of antiquity, the Pharos (lighthouse), at 140 meters high, stood on the island with the same name, in front of the harbor, and showed the way to the ships that carried valuable goods from all over the world.

Δ Δ Δ

4. The Casing Stones

Δ The core masonry of the pyramids were dressed with casing blocks made of fine-grained limestone that appears to be polished, and which would have shone brilliantly in the Egyptian sun.

Δ The four sloping faces of the Khufu Pyramid were originally dressed with 115,000 of these casing stones—5.5 acres of them on each of its four faces. Each weighed ten to fifteen tons apiece. The Greek historian Herodotus stated that the joints between them were so finely dressed as to be nearly invisible. A tolerance of .01 inch was the maximum found between these stones—so tight that a piece of paper cannot fit between them.

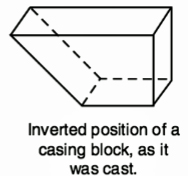

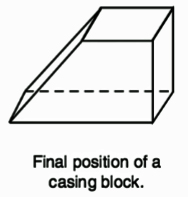

The casing blocks in the 4th Dynasty pyramids were angled to produce the slope of the pyramid. Because of their shape, the casing blocks were cast in an inverted position against neighboring blocks. Once they hardened, the concrete forms were removed and the blocks were then turned upside down and positioned.

To reinforce the evidence of such a technique, researchers found that the inscriptions on the casing stones of the Red Pyramid of Snefru and the Khufu (Cheops) Pyramid are always on the bottom of the casing blocks. This is good evidence that they were cast in the inverted position. Had the casing blocks been carved, inscriptions would be found on various sides, and not just one position.

Δ Δ Δ

5. Additional Evidential Facts Of Synthetic Pyramid Blocks

Some earlier points are worth repeating here to complete the context of the subject matter. As stated earlier:

a. There are about ten standard block lengths throughout the pyramid. Similarly, limited numbers of standard sizes apply in other pyramids as well. Carving such highly uniform dimensions is impossible. However, having standardized concrete forming molds is a more logical conclusion.

b. Another affirming fact of how long some blocks are is that the longest blocks in the pyramids always have the same length. This is extremely strong evidence in favor of the use of casting molds.

To add to the evidence that the blocks were are not natural stone but high-quality limestone concrete (synthetic stone) which was cast directly in place, let us consider the following undisputed facts about the Khufu (Cheops) Pyramid of Giza. [Similar facts to those mentioned here are also applicable to all masonry pyramids.]

1. The perfectly fitted millions of blocks can be achieved by molding and forming concrete blocks.

2. In 1974, a team from Stanford Research Institute (SRI) of Stanford University, used electromagnetic sounding equipment to locate hidden rooms. The waves, when sent out, were absorbed by the high moisture content of the blocks. As a result, the mission failed.

The question is then: How can the pyramid attract moisture in the midst of an arid desert area? The answer is that only concrete blocks retain moisture, which is further evidence showing that the pyramid blocks were synthetic and not quarried.

3. The French scientists found that the bulk density of the pyramid blocks is 20% lighter than the local bedrock limestone. Cast blocks are always 20-25% lighter than natural rock, because they are full of air bubbles.

4. The paper-thin mortar between the stone blocks does not provide any cohesive power between the stone blocks. This paper-thin mortar is actually the result of excess water in the concrete slurry. The weight of aggregates in the concrete mix squeezes watery cement to the surface, where it sets, to form the thin surface mortar layer.

5. Organic fibers, air bubbles, and an artificial red coating are visible on some blocks. All are indicative of the casting process of man-mad (not natural) stone.

6. The top layers of several blocks are quite riddled with holes. The deteriorated layers look like sponges. The denser bottom layer didn’t deteriorate. In a concrete mix, air bubbles and excess watery binder rise to the top, producing a lighter, weaker form. The rough top layer is always about the same size, regardless of the height of the block.

This phenomena is evident at all the pyramids and temples of Giza; i.e. lightweight, weathered, and weak top portions which are indicative of cast concrete, and not natural stone.

7. The largest blocks, found throughout the ancient Egyptian monuments of Giza, exhibit many wavy lines and not horizontal lines. Wavy lines occur when concrete casting is stopped for several hours (such as an overnight stoppage).The earlier casted concrete consolidates, and the result is a wavy line that develops between it and the next concrete pour/cast. Strata in the bedrock are horizontal and straight, while wavy lines result when material is poured into a mold.

8. Modern mortar consists exclusively of hydrated calcium sulfate. Ancient Egyptian mortar is based on a silico-aluminate, a result of geopolymerization.

9. These perfectly fitted man-made concrete blocks are not limited to the pyramids, but are found in hundreds of tomb chapels in Giza and elsewhere.

And here we also find no vertical joints and the blocks fit perfectly.

10. The huge paving blocks that surround the pyramids are likewise fitted perfectly—which is made more difficult by the Egyptians’ intention of not having continuous cracks. So we have perfectly fitted, huge, irregularly-shaped blocks that can only be made of man-made concrete mix.

11. The only surviving record of the activities of Khnum-Khufu’s reign are scenes engraved in Sinai, indicating extensive mining expeditions of arsenic minerals required for making stones.

Δ Δ Δ

[An excerpt from Egyptian Pyramids Revisited by Moustafa Gadalla]