The Pharaoh ‘s Role – The Master Servant

1. The Eternal Power

Contrary to the Bible and Hollywood’s distorted image of the pharaoh as a harsh tyrant living a luxurious, useless, and easy life, the pharaoh had no political power, lived in a mud-brick dwelling, and spent his time performing his duty to act as intermediary between the natural and supernatural worlds by conducting rites and sacrifices.

Pharaohs were not expected to be leaders of victorious armies, but were expected to secure a regular succession of rich harvests.

The pharaoh was the source of prosperity and well-being of the state, to his people. He was their servant; not their tyrant. He laid the seeds at the beginning of the season and collected the “fruit” at harvest time. He spent his time serving the interests of his people by performing necessary rituals throughout the whole country. The pharaohs were identified with the crops and were addressed as: Our Crop and Our Harvest.

Based on his extensive training with the powers of the supernatural, the Pharaoh’s body was believed to be charged with a divine dynamism that communicated itself to everything he touched. Diodorus reported that the Pharaoh typically led a restricted life. Not even the most intimate of his courtiers might see him eat or drink. When the King ate, he did so in private. The food was offered to him with the same ritual as was used by priests in offering sacrifice to the neteru (gods, goddesses).

The right to rule was considered to be a continuous chain of legitimacy which was based on matriarchal principles where the line of royal descent in Egypt was through the eldest daughter. Whoever she married became the pharaoh. If the pharaoh did not beget a daughter, a new “dynasty” was formed. There was no “royal blood” in Ancient Egypt.

The eternal power of the leader/King never dies. The power is merely transferred from one human body to another human body (medium). Accordingly, all the Pharaohs identified themselves with Horus as a living King and with the soul of Osiris as a dead King.

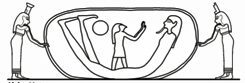

This is eloquently illustrated in several places in Ancient Egyptian tombs and temples, as shown below, whereby Horus is being born out of Osiris after his death.

Even the British of today follow, unconsciously, the same belief that the eternal power transfers from one human body to another, when they say:

“The king is dead. Long live the king.”

as if to say:

“Osiris is dead. Long live Horus.”

2. The Master Servant

The Ancient Egyptian King, with the help of the priests associated with him and via the ancestral spirits, established a proper relationship between the people and the supernatural forces. The leader was regarded as having a personal influence over the works of nature, to whom divine honors were paid and to whom divine powers were attributed.

The Ancient Egyptian Pharaoh was an earthly image of the sum of divine energies of the universe (neteru). As such, he continually performed the necessary rituals for proper relationship and communication with the neteru (the powers of the universe) in order to maintain the welfare of the state and to insure the fertility of the earth, that it may bring forth sustenance.

Each year, the King hoed the first plot of farming land and sowed the first seeds. If the Pharaoh did not perform the daily liturgy to the neteru (gods, goddesses), the crops would perish. He spent his time performing his duties to his people by performing the necessary rituals, from one temple to another, throughout the whole country.

Despite the repeated charges of vanity against the Pharaohs, it is worth remembering that their abodes while on earth were never made of stone, but of mud brick, the same material used by the humblest peasants. These humble mortal monarchs believed that the impermanent body, formed of clay by Khnum, the ram-headed neter, called for an equally impermanent abode on this earth. The earthly houses of the Kings have long since returned to the earth from which they were raised.

3. Keeping The Flame Alive [The Heb-Sed Festival]

The fertility of the soil, the abundant harvests, the health of people and cattle, the normal flow of events, and all phenomena of life were/are intimately linked to the potential of the ruler’s vital force. It is therefore that the Egyptian king was not supposed (or even able) to reign unless he was in good health and spirits. Accordingly, he was obliged to rejuvenate his vital force by regularly attending physical and metaphysical practices which are known as the Heb-Sed rituals.

The purpose of the Ancient Egyptian annual Heb-Sed festival (which was regularly held towards the end of December) was to renew the pharaoh’s power in a series of rituals including ritual sacrifice. The renewal rituals were aimed at bringing a new life force to the king; i.e. a (figurative) death and a (figurative) rebirth of the reigning king. One of the Heb-Sed rituals was to induce a near-death experience so that the king could travel to the higher realms to rejuvenate his cosmic powers. When he returned, he would be a “new” king. This gives more meaning to the phrase:

The King is dead—Long Live the King.

4. The People Rule

The Pharaoh’s conduct and mode of life were regulated by prescribed rules, since his main function was to ensure the prosperity and well-being of his subjects. Laws were laid down in the sacred books for the order and nature of his occupations.

He was forbidden to commit excesses. Even the kind and quality of his foods were prescribed with precision. Even if the king had the means of defying prescribed rules, the voice of the people could punish him at his death by the disgrace of excluding his body from burial in his own tomb.

When the body of the deceased king was placed in state near the entrance of his tomb, the assembled people were asked if anyone objected to the king’s entombment because he did not perform his duties. If the public showed their dissent by loud murmurs, he was deprived of the honor of the customary public funeral and burial in his tomb.

The body of an unaccomplished Egyptian pharaoh, though excluded from the burial at the necropolis, was not refused his right to be buried somewhere else. A case in point is the communal gravesite that was found in 1876 in the immediate vicinity of the Hatshepsut Commemorative (wrongly known as “Mortuary”) Temple on the West Bank of the River Nile at Luxor (Thebes). Those whose performances were unsatisfactory to the common populace were buried at this location. Such rejected pharaohs included the mummies of well-recognized and influential names such as Amenhotep I, Tuthomosis II and III, Seti I, and Ramses I and III.

As will be shown later in this book, Egyptian texts clearly state that the Egyptian king can only have his place in Heaven if he:

“hath not been spoken against on earth before men, he

hath not been accused of sin in heaven before the neteru (gods, goddesses).”

5. The Victorious King

In Ancient Egyptian temples, tombs, and texts, human vices are depicted as foreigners (the sick body is sick because it is/was invaded by foreign germs). Foreigners are depicted as subdued—arms tightened/tied behind their backs—to portray inner self-control.

The most vivid example of self control is the common depiction of the Pharaoh (The Perfected Man) on the outer walls of Ancient Egyptian temples, subduing/controlling foreign enemies (the enemies [impurities] within). It symbolizes the forces of order controlling chaos and the light triumphing over darkness.

The same “war” scene is repeated at temples throughout the country, which signifies its symbolism and is not necessarily a representation of actual historical events.

The “war” scenes symbolize the never-ending battle between Good and Evil. In many cases there is no historical basis for such war scenes, even though a precise date is given. Such is the case for the war scenes on the Temple Pylon at Medinat Habu.

Western academicians are incapable of understanding metaphysical realities, and hence “make” historical events out of metaphysical concepts. The famed “Battle of Kadesh” is really the personal drama of the individual royal man (the king in each of us) single-handedly subduing the inner forces of chaos and darkness. Kadesh means holy/sacred.

Therefore, the Battle of Kadesh signifies the inner struggle—a holy war within each individual.

[An excerpt from Egyptian Cosmology: The Animated Universe, Third Edition by Moustafa Gadalla]

https://egyptianwisdomcenter.org/product/egyptian-cosmology-the-animated-universe-third-edition/